From Field to Printing Plate: How Living on an Arable Farm Shapes My Collagraph Practice

Field Marks: Finding Gold in the Soil Beneath Our Feet

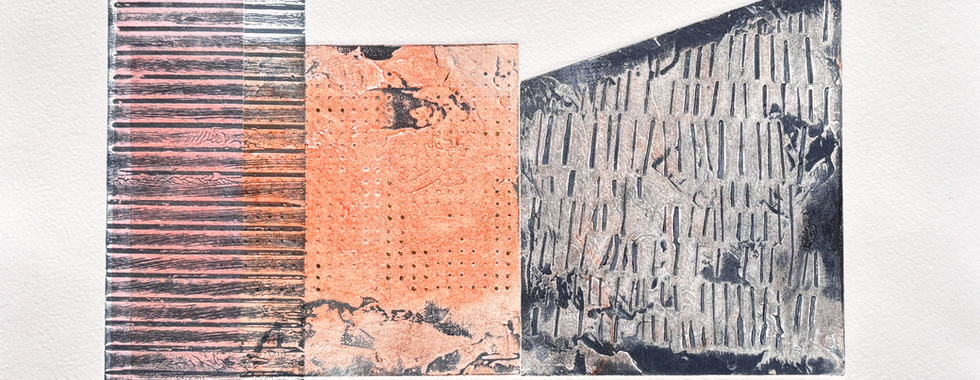

There's a moment just before sunset when light sweeps across Lincolnshire's arable fields, transforming ordinary furrows into lines of unexpected brilliance. This play of light and shadow across our agricultural landscape became the catalyst for my new print series, 'Field Marks' - a collection of collagraph prints, where 24ct gold accents illuminate the patterns of worked soil.

As a printmaker, I've long been fascinated by what we deem precious. While others might look to more obvious treasures, I find myself increasingly drawn to things in nature as my treasure- a frost decorated fern, a bluetit seeming to meet my gaze when bouncing on a dried stem, or what lies directly beneath our feet - soil, that vital yet often overlooked foundation of life.

The documentary "6 Inches of Soil" powerfully reinforced this perspective, highlighting how this thin layer of living earth sustains our entire food system and, by extension, our existence. Through these prints, I'm attempting to elevate soil to its rightful place in our collective consciousness - as something truly precious, worthy of both artistic celebration and more careful stewardship.

I recently discovered a new tool which is great for us collagraph makers. The scalpel is a familiar tool for a collagraph maker, but comes with obvious dangers, and my fingers are a rather invaluable commodity!

Having recently had an A and E trip with my hubby, with his more renagade scalpel use, I did some research to see if there were any blades which might not result in hospital visits. That was when I discovered the ceramic blade by 'Slice'. I have had it a number of months now and thought I would put it through its paces before writing about its use, so here goes.

The website I bought it from laid out certain claims... eg unlike traditional metal blades, ceramic blades stay sharper for longer and are rust-proof. They're incredibly precise, making clean cuts through various materials without dulling quickly. The ceramic material also means they're lighter than metal blades, reducing hand fatigue during intricate cutting work. Additionally, they're non-conductive and non-magnetic, which can be beneficial in certain artistic and technical applications.

As a collagraph maker, the Slice ceramic blade provides a safer alternative to traditional scalpels. The blade's design minimises the risk of accidental slips and cuts, giving me more confidence while working with delicate materials. The blade's edge is sharp enough for precision work but with a safety profile that significantly reduces the likelihood of me injurying myself. Genuinely, you can run the blade across your finger and it remains cut free- thankfully!

In my work, I cut lines and shapes from mountboard to display the 'fluffy' surface below or create my own stencils to push media through with more confidence, as well as stencils from cereal packets, which are surprisingly sturdy, or sometimes with mylar for when I know I will use a stencil repeatedly, knowing it can be easily washed.

Here is a link to where I bought the slice pen- one with a rounded tip, the other more pointed.

The first blade I bought has a cap which I have mislaid a few time but the updated verion is improved in that the lid is incorporated so cannot be lost.

I much prefer this pen.

And this is where I get the replacement pointy blades

I first bought the rounded blades but for collagraph the pointed ones are more effective for my use.

Incidentally, I also bought a safety cutter for opening parcels, which I have also found useful.

As a collagraph maker, I interpret field marks in several ways. The deep, shadowed grooves are replicated by applying a thick, gritty carborundum onto the mount board surface, creating a tactile, three-dimensional effect. The contrast between the light and dark areas may be emphasized through the use of other diverse materials, such as woven grasses and

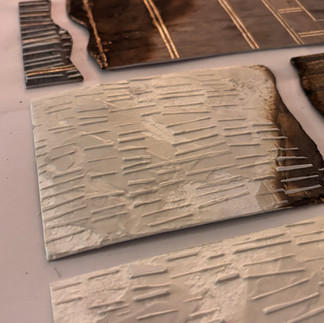

Additionally, the repetitive, rhythmic patterns of the lines can be explored further. By manipulating the spacing, density, and direction of the lines, I experiment with different compositional arrangements, creating a sense of movement and depth on the print. The interplay of light and shadow, may be translated through intentional inking and wiping techniques, allowing some control but leaving some surprises from the print gods. Some of my plates are also given natural looking edges though my burning of them. I obviously did this safely outside and a very curious delivery driver had lots of questions to ask when he arrived during this task!

My agricultural landscape offers a rich source of inspiration for me with the potential to capture the tactile qualities of the field's surface, while also thinking of the more general marks that we as humans leave on our environment.

Inspired by "Six Inches of Soil" and intimate portrayal of a newer generation of farmers nurturing the earth, I began to conceptualise a series of intricate prints that capture the delicate layers, textures, and living essence of soil. My artwork is becoming a passionate visual testament to the ground beneath our feet.

Incorporating stems and grasses amplifies the connection between image, process, and a felt sense of being rooted in the environment. It's an approach that infuses my collagraph with authenticity and place.

Nature's Patterns, My Touches

At a recent print fair, I experienced one of those affirming moments that remind artists why we create. A garden designer purchased one of my prints, and our conversation quickly turned to our shared appreciation of Piet Oudolf's revolutionary approach to landscape design. A dear friend years ago introduced me to his work with a gift of the book, Oudolf Hummelo A Journey Through A Plantsman's Life.'

Like Oudolf, who considers each site's soil and natural patterns to create his naturalistic plantings, I find myself studying the rhythms of a landscape - the geometric precision of planted rows softened by natural growth, the seasonal transitions from bare earth to emerging life, and the way human practices create their own environmental art.

The Art of Soil

My collagraph process mirrors the soil structures I'm exploring. Just as soil builds up in distinct layers - each with its own texture and purpose - I build my printing plates through careful layering on mountboard substrates. Each layer I add to the board links to the complex strata of agricultural soil: the surface textures might evoke the crumbling tilth of worked earth, while deeper cuts and marks suggest the hidden networks of roots and soil life below.

The addition of 24-carat gold leaf brings an different dimension to the work and links back to my 'What is Precious' theme. Using water-based size, I carefully apply this exquisite material.

Each collagraph in this series employs these minimal yet meaningful markings to capture agricultural patterns - furrows, seedling rows, and the interplay of light across worked soil.

Living Within the Pattern

Our home, nestled in the heart of an arable farm in Lincolnshire, puts me at the center of agriculture's rotating canvas. The seasonal shifts aren't just changes in temperature or light - they're transformations written in the soil.

Seed drills create sketchy, linear compositions across fields that were, just weeks later, a more chaotic tangle of harvest stubble. These transitions fascinate me.

The landscape has transformed over the years, reflecting shifting agricultural priorities.

Where dairy cows once grazed, (the farm where we live is even called Dairy farm still and locals recall a bull iin being housed in what is now our kitchen) now stands a tapestry of diverse crops.

Towering miscanthus sways in the breeze, its tall stems creating dramatic shadows that change with the sun's arc.

Sugar beet fields offer a different rhythm - their broad leaves forming dense patterns broken by precise irrigation lines.

The leek fields present yet another geometric adventure, their straight rows marching toward the horizon with more precision.

The Marks of Agriculture

Sugar beet introduces its own vocabulary of marks. The lifting process reveals root patterns in the soil, temporary installations that exist for moments before being smoothed away. These fleeting marks find permanence in my collagraph plates, where I build layers of texture to echo the complexity of the disturbed earth.

Leek fields are perhaps the most mesmerising in terms of pattern. Their regimented rows create shadow plays throughout the day, while irrigation systems add another layer of geometric complexity. These agricultural lines become deeply carved grooves in my plates, capturing both the precision of modern farming and the organic variations that nature inevitably introduces.

The Process of Capture

The process of building up textures on my plates mirrors the layered history of the land itself. Just as the fields hold memories of previous crops and changing farming practices, my plates accumulate textures that tell stories of the landscape. some of the marks you see above are raised lines, while others are pressed in and I welcome this contrast on finished pieces.

The changing seasons bring their own distinctive rhythms to both the fields and my printmaking practice. Spring sees the emergence of young shoots, their patterns offering delicate textures that I capture by creating my own stencils which I push pastes through and also through careful scoring. Summer brings mature crops - the sugar beet's broad canopy creating a patchwork of light and shadow that translates into deeply textured plates.

Autumn harvest transforms the landscape again. The cutting of miscanthus reveals geometric patterns in the stubble, while lifted sugar beet leaves behind abstract patterns in the soil. These moments of transition often inspire my most complex plates, layers of texture building upon each other just as the farming year builds layer upon layer of pattern in the fields.

Winter brings its own stark beauty. Frost outlines the remnants of harvest patterns, while newly ploughed fields wait for their next planting. This is often my most productive printing season, as the stripped-back landscape reveals its underlying structures most clearly.

Each collagraph plate becomes my field, my tools echo the changes and, in this way, my printmaking practice becomes not just a recording of agricultural patterns, but a participation in the ongoing story of our relationship with the land.

What Is Precious?

In 2024 I was part of a Design Nation sustainable and ethical practice group exhibition, where I was asked about my recent work, both in earth pigment on linen and collagraph marks on paper, responding to the title of the exhibition, 'What Is Precious?'.

This recent work explores the commitment to my motto, "Make a mark and mark what you make."

To see more of my collagraph work inspired by modern agricultural landscapes, visit my website - the art prints area or join one of my printmaking workshops where I explore texture, pattern, and the connection between place and artistic practice.

Kommentare